Doug and Chris had attempted the line earlier that season

and climbed to within a pitch of the summit plateau. It was dark and storming

hard as they traversed the final rock wall guarding the top and a fairly straightforward descent down a gully to the North. They could hear the wind raging

like a freight train above them, and despite their desperate search for a

possible exit (a crack, a corner, a chimney, anything!) their headlamps

revealed nothing but smooth granite staring back at them. Without bivy

equipment or a stove, they had to keep moving to avoid freezing, and unable to

find the fabled crack that lead to the top, they had to begin rapping

immediately. Doug would leave a good chunk of his rack on that wall during eleven

seventy meter rappels to the snowfields below, where exhausted, wet and cold,

they found a bivy cave and passed the few remaining hours until sunrise

snuggling and doing sit-ups to stay warm.

So, Sheridan invited

me to join him for another go at Taylor’s Central Buttress. Doug and I are training in his small garage,

which is packed full of free weights, climbing gear, and a small forty five

degree systems board.

Oh yeah?

Yep, and Jack Roberts

is apparently coming along as well.

Have you ever met Jack?

I’ve never met either

of them.

They’re both good

guys. Sheridan is climbing super strong and is always psyched, and Jack… well

Jack is Jack Roberts for Christ sake. Not only has he been crushing it for decades, he’s just one of the nicest guys you’ll meet.

Yeah, that’s what I

hear.

The route is big

though… probably bigger than anything else in the Park. Get an early start.

It’s dark, it’s cold, it’s windy. It’s the usual RMNP winter

alpine-start requiring a high-commitment exit from your vehicle at the always

gusty Glacier Gorge Trail Head - where cars rock back and forth in the gale and

red eyed climbers crank everything from Slayer to Wu Tang to The Be Good Tanyas

and gulp down last minute mouthfuls of strong coffee, knowing fully well

they’ll probably have to shit within the first quarter mile or so of hiking...

We walk through the forest following the snow-shoe highway towards the Loch. At

first we chitchat, and I feel awkward around these two men who are so much

older, more experienced, and more accomplished than I. As the miles go buy we separate by bits of

personal space, our heads down, our lungs burning, our minds all thinking

separate thoughts – each of us is in our own world. Mine is a dream world as I

walk across the frozen lake, my headlamp illuminating air pockets and hairline

cracks - the ice varying shades of blue. I’m terrified of not performing today,

of not climbing well, of not keeping up, I fear they will not like me.

It isn’t long before Chris and I are far ahead, past the

Loch, slogging up towards Timberline Falls below Lake of Glass and Sky Pond. We

stop for water and some food and watch the sky come to light, the shapes of

walls and pillars emerge from the darkness. Chris tells me about Jack’s feet – the

bane of his existence and the result of a lifetime wearing mountain-boots and

climbing shoes, of enduring frostbite, immersion foot, countless hours spent

kicking steps and front-pointing in hard ice. I remembered reading a story told

by Dougald McDonald about Jack having to cut slots in his already roomy

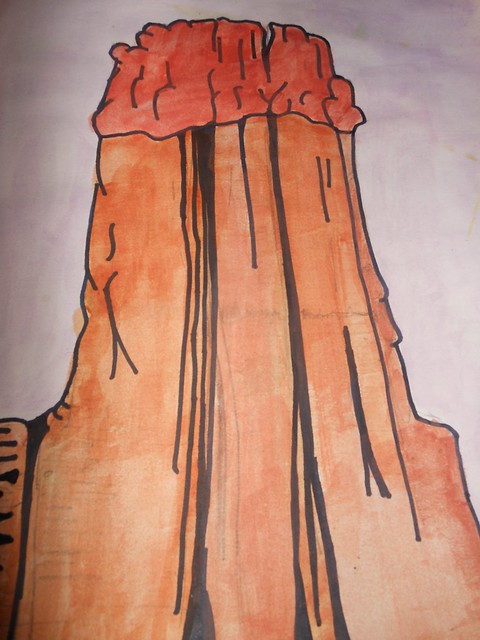

climbing shoes to relieve the pain while climbing a new route on Devil’s Thumb

in the Indian Peaks Wilderness. Jack still managed to lead the route’s runout

5.10 crux pitch in style. Chris tells me how Jack placed pads between his toes

and rapped his feet in cloth that morning on the drive up. Damn – I think, but at the same time I’m worried. It’s nearly light

and we have a ways to go before we reach the base of our route.

There’s a sense of dread floating around in my head. Maybe

it’s just all the talk of epics and suffering on Taylors Central Buttress, talk

of difficult mixed climbing, deadly runouts and dangerous snow-covered slabs.

Maybe it’s the fact that I’m climbing with two people I’ve never met before

this day. Maybe I’m still nervous about performing well and leaving a good

impression on these two climbers who’s accomplishments I so respect. I slog on

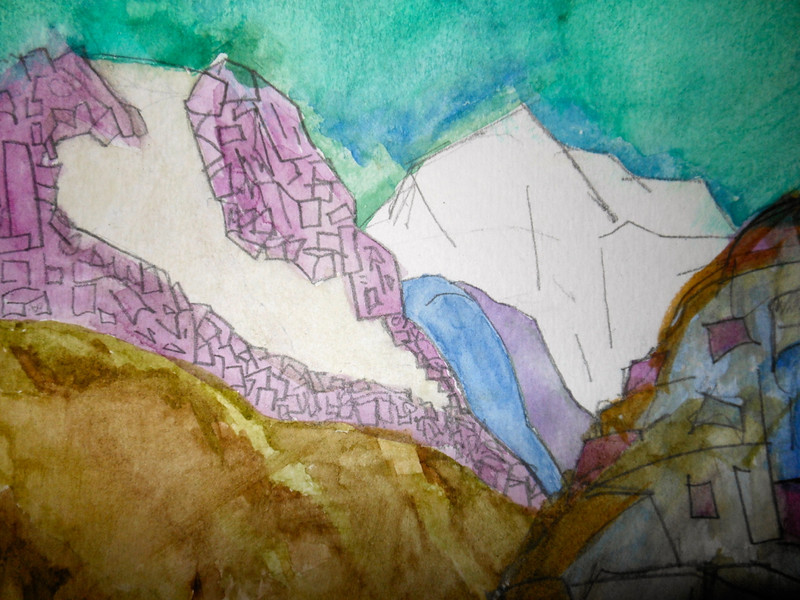

towards Sky Pond, the Cathedral Spires rising on my right, Vanquished Buttress

and Powell Peak to my left, the Central Buttress of Taylor rising before me,

growing bigger and bigger and more scary. These mountains are nothing to Jack

and Chris, who have climbed the world over, and who’s accomplishments have

graced the pages of history and influenced the lives of so many of their peers,

but to me this mountain is massive, the face a daunting pile of choss covered

in unconsolidated snow.

We rested again at a boulder beneath the final snowfield

leading up to the face. Jack is a small dot below, slowing but surely gaining

ground. Chris and I stash our gear and snowshoes beneath the boulder, rack up

for the climb, and then proceed towards the cliff, slogging upwards through knee deep snow. Jack will be here by the time you lead the

first pitch, says Chris. Apparently I’m leading the first pitch. After

nearly falling into a moat guarding the base of the wall, I carefully

dry-tooled up a steep rock step to reach a ramp of snow leading up and right

towards the Central Buttress. The snow

of course was barely consolidated and resting on a granite slab – terrifying

stuff. I groveled up the steep snow, digging for rock edges to hook and

searching vainly for protection. I’ve

never before or after climbed such steep powder snow and the thought of it

peeling off in a cohesive slab made me tense. About half a ropelength up the

ramp I found a hairline crack and pounded in a knifeblade as far as it would

go, (about an inch), promptly tied it off and continued upward. A large

chockstone loomed above me. I had an eerie feeling as I gently moved up the

impossibly steep powder snow. Occasionally I would find footholds on the

granite slabs to my sides and I stuck my tools sideways into the snow as deep

as I could to gain purchase. At last I reached the chockstone, beneath which

lay a small cave. I practically dove for it’s safety as the snow disintegrated

around me. It wasn’t a difficult pitch, it was tedious, and it was very

dangerous. I found little protection for a belay, just one decent spectre

driven into a clump of frozen turf and a number three Camelot slotted deep in a

flaring, iced over crack, but the cave its self seemed a good natural stance to

belay from, so I began to bring Jack (who had arrived at the base long before I

finished my lead) and Chris up to the cave. Within minutes I heard a shout and

felt one of the half ropes go tight – I looked in horror as the Spectre twisted

in the turf and the cam expanded in the flare, holding, but obviously strained.

The snow had finally peeled off the slab, taking Jack for a short ride, but he

was fine.

I passed the rack to Chris and settled into my belay jacket. Jack was eating a cliffbar. I felt very glum. Jack’s fall had proven real the

danger I had sensed on the previous pitch, and it was already noon… the short

days of December combined with the deep unconsolidated snow made the likelihood

of reaching the notorious last pitch before dark seen unrealistic. I had class

in the morning and knew my folks would be freaking out if I didn’t call them

from Estes before midnight (they’re from New Jersey and just don’t understand

the idea of a forced bivouac, of waking up so early to go climbing, are

skeptical when I tell them cell service in the Park is scarce, and just plane

hate me climbing. Eventually my dad would buy me a Spot PLB and insist I carry

it I were to continue living under his roof… needless to say I fucking hate

that thing and don’t use it anymore…) I kept my sense of futility to myself

however, and Chris – who I was quickly learning is always psyched and

never afraid to suffer a bit – set off up a difficult M6ish corner around the

chockstone. I was impressed by his tenacity and grace as he quickly climbed the

pitch, torqueing his picks in a thin crack and finding the tiniest edges for

his front points. He protected the line with hard won RPs and knifeblades

slotted into tiny seams along the way.

I took the opportunity to spend a few minutes talking to Jack,

who seemed quiet and content, just happy to be out in the mountains climbing.

We talked about mixed climbing in the mountains and how different it is from

cragging at a place like Vail, or Ouray. Groveling up these alpine routes in

the Park required a broad array of skill that made the pursuit more dynamic,

more dangerous, and to some more rewarding. Open up any American climbing

magazine and you’re led to believe that alpine climbing is dead or never

existed outside of Alaska, Canada, Europe, and the Himalaya. Ice climbing is

alive and well, but you rarely find it here in the high peaks. Winter ice is

all about frozen waterfalls and spring or aquifer fed drips. Ice in the alpine

forms early in the Fall and late in the Spring and come from melt-freeze cycles

and feeder slopes of snow. Winter climbing in RMNP is more akin to Scottish

climbing (minus the 100% humidity) and mostly involves dry-tooling, turf

sticks, and sketchy unconsolidated snow climbing. It involves long days, long

approaches by foot or ski, a very active and dangerous snowpack, full on

mountain weather (RMNP is often referred to as The Patagonia Training Center, and is widely regarded as one of the

windiest places in the West) spindrift, and climbing traditional alpine rock

routes, but with tools and crampons in place of sticky rubber and chalkbags.

RMNP is the perfect venue for such an adventurous form of climbing – it’s not

really popular, nor is it likely to be, but it is my favorite form of climbing

and RMNP is my favorite place. A couple years later, after many more

fine climbs with the likes of Sheridan, Doug, and my friend Ryan – I would

begin my cancer journey, and these guys with whom I had shared such fine adventures

would remain my most encouraging, most supportive of friends. A true testament

to the “brotherhood of the rope”.

I don’t know what Jack Roberts thought of me. I was keen to

ask him questions about his routes in the Alps and Alaska Ranges, and about his

life guiding. He was extremely modest about his accomplishments and honest

about the difficulties facing a professional mountain guide. He seemed happy

though, and I imagine he was an excellent guide, someone who wasn’t afraid to

share their passion for the mountains with others for fear of loosing some of

their own.

The second pitch was indeed difficult, and the fifty feet or so of steep rock gave way to more steep and deep slogging. I think it was about noon when Jack and I finally reached Chris’s belay. Above us lay about eight more pitches. I voted for bailing, considering the time and conditions, Chris was psyched to continue onward, or maybe traverse left to an easier route called Quicksilver, and Jack said he could go either way – although he did admit we might be in a “world of hurt” if we continued – which assured me I wasn’t being unreasonable. We thought it over for a while but my sense of doom and the thought of spending another night rapping down wet icy ropes (I had recently endured a 24 hour epic day involving a lot of wet and cold rappels on McHenry’s) won out. “Fuck it dude, let’s go to Ed’s Cantina”. So we rapped off, conveniently using two of Doug and Chris’s old bail anchors.

The second pitch was indeed difficult, and the fifty feet or so of steep rock gave way to more steep and deep slogging. I think it was about noon when Jack and I finally reached Chris’s belay. Above us lay about eight more pitches. I voted for bailing, considering the time and conditions, Chris was psyched to continue onward, or maybe traverse left to an easier route called Quicksilver, and Jack said he could go either way – although he did admit we might be in a “world of hurt” if we continued – which assured me I wasn’t being unreasonable. We thought it over for a while but my sense of doom and the thought of spending another night rapping down wet icy ropes (I had recently endured a 24 hour epic day involving a lot of wet and cold rappels on McHenry’s) won out. “Fuck it dude, let’s go to Ed’s Cantina”. So we rapped off, conveniently using two of Doug and Chris’s old bail anchors.

We all walked out together at a slow casual pace, commenting

often to one another at some beautiful sight – a bird, a thin line of ice

running down the Petit Gully, the clouds building behind the Sharkstooth. We

talked about women and climbing and Jack mentioned how difficult climbing and guiding can be on a relationship, and said “get out of it while you can, Kevin. Get out of it while you can!” A

few minutes down the trail he turned to me and said “it’s probably too late though, eh?” We laughed and Jack told Chris

and I about Ecuador, where he would soon be guiding clients up volcanoes. He

talked about how his wife Pam, had spent the day skiing by herself, and how

fortunate he was to have a wife who loved the mountains and was understanding

when it came to travelling. He said: "she’s

pretty good at taking care of herself". I asked him about all the routes in RMNP that he had climbed over the years and made a mental note to remember the ones he spoke

most fondly of. When we stopped for

water and food I was surprised to see him pull a large stainless steel thermos

from his pack and pour himself some tea. I guess light is right, but weight can

be great. Like all professional alpinists he seemed comfortable and at ease,

quickly shedding a layer while his tea cooled, he echoed my earliest mentor Ed

Crothers with the adage “sweating is for

amateurs”. His systems were so dialed he accomplished his tea-break and

layer change in the time it took me to remove my pack and take a quick drink of

water (after spending five minutes fumbling around in my pack looking for the

bottle). At dinner in Estes, he spoke fondly about his early days wall climbing

in Yosemite, his eyes glowing with countless memories of days and nights spent

on walls, making the second ascents of The Shield, Zodiac, Tangerine Trip,

Mescalito, and more. He said that wall climbing was great for his free

climbing, that he’d spend a week on a wall hauling, jugging, hammering iron,

and that he’d feel lighter and stronger when he was done. I practically blushed

when he complimented me on my knifeblade placement earlier that morning - The best piton placement of the day, for

sure.

After dinner we all shook hands and went our separate ways.

I never saw Jack Roberts again, although Chris and I continued to climb together

and had several excellent adventures that season as well as the following. His

ambition, skill, and devotion to climbing in RMNP is rivaled by few. I am

grateful for his friendship and the adventures we’ve shared. The day Jack,

Chris, and I attempted the Central Buttress on Taylor Peak, a climber was

killed in a fall on a route called “All Mixed Up” just one drainage over from

us. Climbing in the mountains is a rewarding, worthwhile pursuit, but it is

dangerous - brilliantly so – and that is why so many of us love it. The risks

we take enrich our lives and remind us of our own fragility, our own mortality.

I was in the hospital fighting for my life when I heard the news about Jack

Robert’s death. Looking back to that day in the Park I wish that I hadn’t been

the one who wanted to go down. I wish we had continued, I wish I could have had

at least a few more hours with that man. While the climbing community mourned

his loss, I felt his death (a fall taken while climbing Bridal Veil Falls) was

a testament to an amazing lifetime spent climbing, a lifetime spent taking and

accepting risk. In the cancer ward at Presbyterian St. Luke’s Hospital where

individuals even younger than I were dying everyday, Jack’s death seemed right,

like a good way to go. Some people mock the “he died doing what he loved”

thing, but when it comes to Jack Roberts, he surely did and I’m glad I was

fortunate enough to have met him.